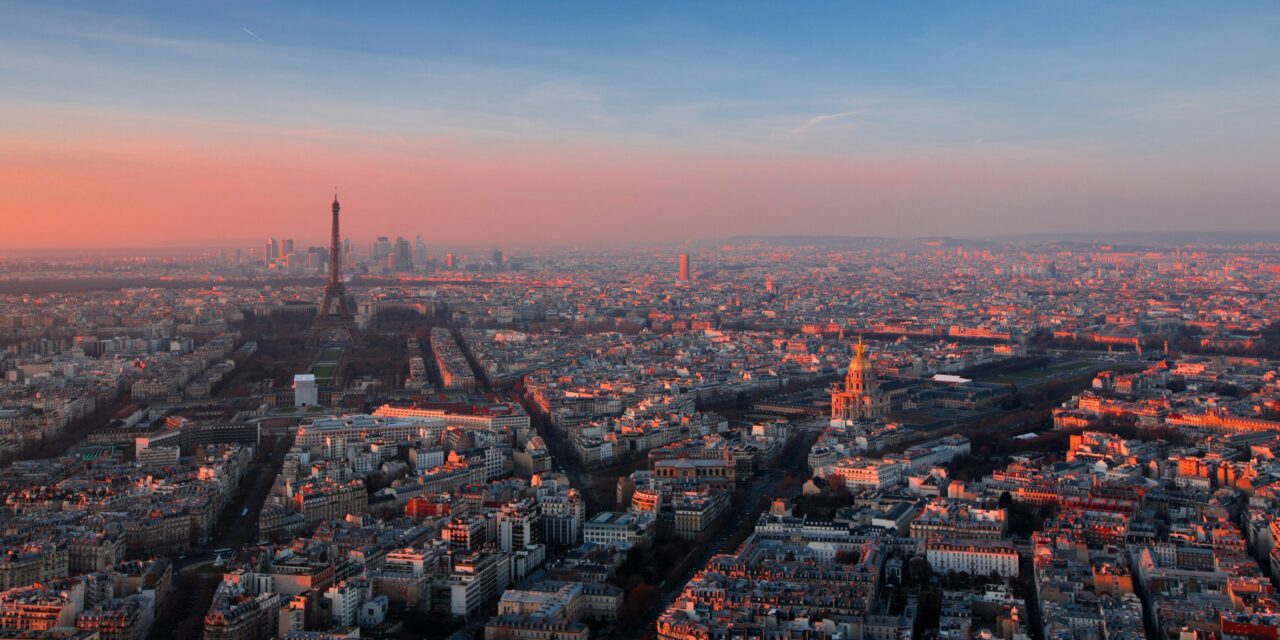

The Paris Agreement is the result of the 21st COP (2015) to UNFCC. It is a legally binding instrument that builds up upon its predecessor – the Kyoto Protocol to UNFCC (COP3, 1997) – and whose purposes are to keep “the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels”, to enhance States’ abilities to “adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience”, and to make “financial flows” consistent with these goals.[1]

In my opinion, one of the most important strengths of the Paris Agreement mainly compared to the Kyoto Protocol resides in the fact that it no longer discriminates between developing and developed countries in terms of their need to be engaged in the common fight against climate change. Whereas the Kyoto Protocol put forward legally binding emission reduction targets for 37 industrialized countries and economies in transition and the European Union, the Paris Agreement does not limit itself to those and adopts a worldwide approach, because all States Parties propose NDCs – “As of March 15,2016, 188 countries had put forward intended nationally determined contributions, representing roughly 95 percent of global emissions.”. This approach was possible and is probable to be successful also because the Paris Agreement has “near universal acceptance”[2], which clearly constitutes another relevant strength. Another bright spot of the Paris Agreement is that the action taken against climate change is set in a progressive manner, meaning that the states have to gradually adapt their NDCs as to increasingly commit to reduce emissions even more, which will lead to continuous development towards the Agreement’s goal, as well as the maintaining of this situation for a very long time.

On the other hand, the Paris Agreement has also some weakness, among which the most relevant one, from my point of view, is the fact that the NDCs are not legally binding, since the legal obligations regarding NDCs are limited to proposing one as a country, but not to achieving the respective NDCs. Therefore, I consider NDCs’ unenforceable nature to constitute a shortcoming of the Paris Agreement, even though the completion of the NDCs is said to be done by states due to the transparency and accountability requirements (meaning that if states do not carry out their commitments in the NDCs, everyone in the international community will find out and pressure upon them will be exerted).

To sum up, I agree with the statement that “The Paris Agreement seeks a Goldilocks solution that is neither too strong (and hence unacceptable to key states) nor too weak (and hence ineffective).”[3]

[1] Paris Agreement to UNFCC (2015, COP21) Article 2.

[2] Daniel Bodansky, ‘The Paris Climate Change Agreement: A New Hope?’ 110:2 American Journal of International Law (2016) 291.

[3] ibid 289.