Whilst this article recognises that the practice of female genital mutilation is still prominent throughout Africa, the Middle East and Asia,[1] it focuses and draws attention to the practice of male genital mutilation within Europe: the circumcision of male infants. Particularly, this article discusses how the UK and Germany have approached the issue with consent. Finally, I deliver my own opinion within the context of international human rights law.

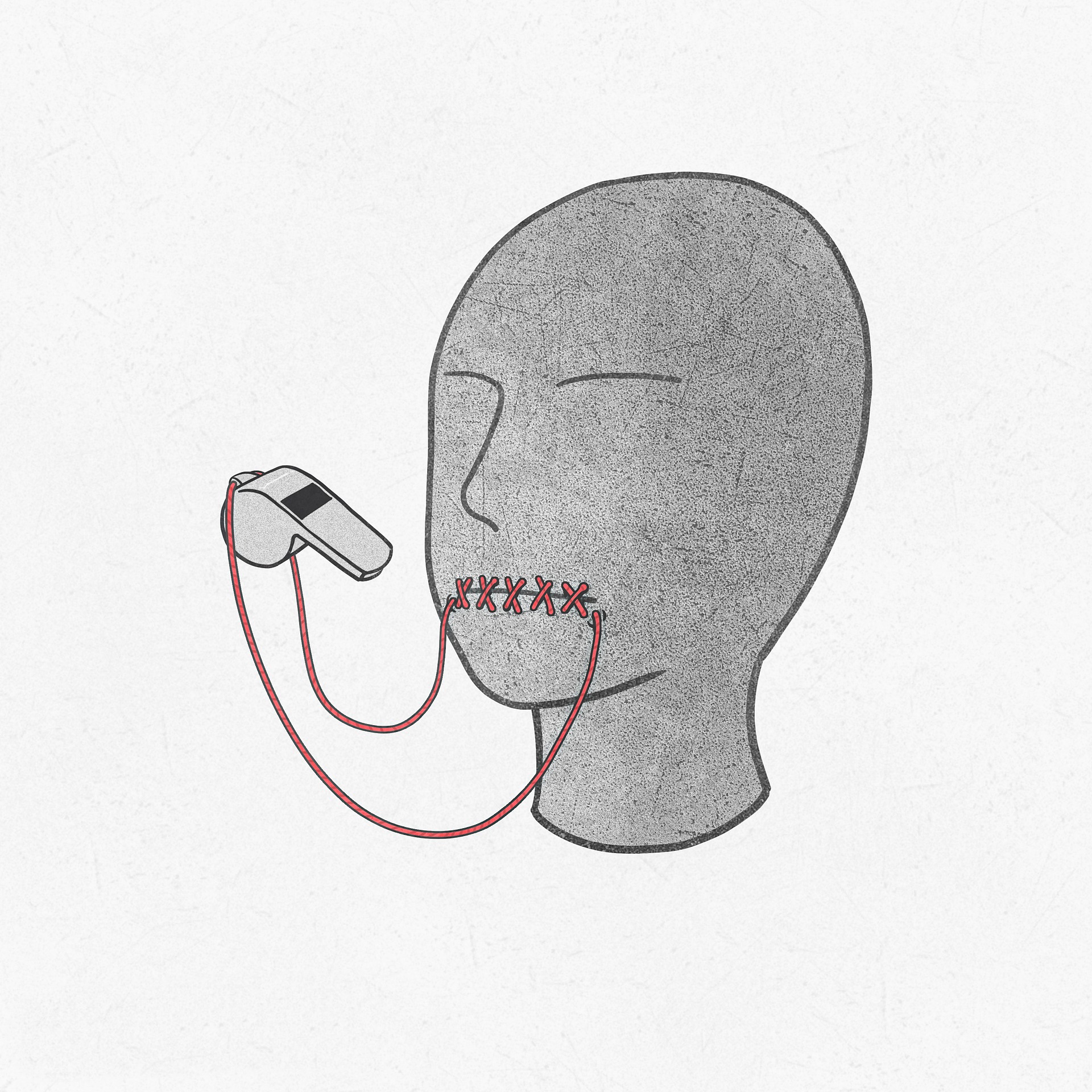

Circumcision is usually performed upon an infant for cultural or religious reasons.[2] For instance, in Judaism, the book of Genesis dictates that the operation must be performed when the infant has reached eight days old.[3] Likewise, in Islam the procedural is also performed before the child has reached the age of majority.[4] Because infants are unable to consent to the operation, consent is given by way of proxy. However, the validity of proxy consent is questionable at the very least namely because; the procedure is irreversible, it violates the autonomy of the child, the procedure is medically unnecessary,[5] and circumcision has been found to repress sexual pleasure.[6]

At the domestic level the approach towards consent varies. For instance, in the UK proxy consent is accepted. In Re J (child’s religious upbringing and circumcision),[7] the Court of Appeal recognised ‘that the operation of circumcision is of considerable consequence and irreversible’[8] and, in the event the parents cannot come to an agreement over circumcising their child, they may otherwise defer to the discretion of the court.

In stark contrast, in 2012 the Cologne Regional Court[9] rejected the notion of proxy consent. The court stated ‘the parents’ right to religious upbringing of their children, when weighed against the right of the child to physical integrity and to self-determination, has no priority, and consequently their consent to the circumcision conflicts with the child’s best interests.’ Furthermore, the court also ruled that ‘[t]he act of the defendant was not justified by consent, either. Consent by the four-year-old was not given and could not be given due to a lack of intellectual maturity. The consent of the parents was given, but could not justify the infliction of bodily harm.’

Thus, whilst there is certainly consensus that the outcome of the procedure should not be taken lightly, the extent to which the autonomy of the child is recognised differs.

In the vein of international human rights law, Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights guarantees the right to physical integrity. In Evans,[10] the European Court of Human Rights found that Article 8 applies to the protection of personal autonomy. In turn, this means that one has the right to refuse medical treatment. Moreover, Article 14 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) safeguards a child’s right to freedom of thought and religion. Finally, Article 3 of the same Convention maintains that public and private social welfare institutions must keep the best interest of the child as a primary concern.

Of course, an infant is unable to consent to medical treatment, let alone refuse it. However, following the logic from the aforementioned provisions, an infant is capable of reasoning to the extent that they are able to determine their own identity. In other words, CRC protects the freedom of thought and religion for a child who has not yet reached the age of majority because it recognises that an infant is capable of formulating such opinions. Thus, the validity of proxy consent would find value should the procedure be postponed until the child is able to have an informed discussion. With that said, the postponement of circumcision is merely a compromise. The ideal situation would be to guarantee freedom from indoctrination, especially when the doctrine, whatever it may be, teaches to brand infants.

[1] World Health Organisation, ‘Female genital mutilation’ (3 February 2020) <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation> accessed 20 Nov 2021

[2] Gatrad, A R et al. ‘Religious circumcision and the Human Rights Act.’ (2002) Archives of disease in childhood vol. 86,2 76

[3] Genesis xvii, 10–13

[4] Ibid (n 2)

[5] Circumcision policy statement. American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Circumcision.’ (1999) Pediatrics 103(3) 686

[6] Kim, D. and Pang, M.-G., ‘The effect of male circumcision on sexuality.’ (2007) BJU International, 99 619-622

[7] Re J (child’s religious upbringing and circumcision) [2000] 1 Family Court Reports 307

[8] Ibid [21]

[9] For the original judgement see: Decision of May 7, 2012 [in German], Docket No. Az. 151 Ns 169/11, Landgericht Köln Cologne. For an English translation see link: https://ukhumanrightsblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/circumcision_eng.doc

[10] Evans v United Kingdom, (App. 6339/05), 10 April 2007, 43 EHHR 21, para. 71.