Over the last couple of years, Brexit has been a hot topic. It seemed new information on the negotiations was released every day, yet somehow Britain and the European Union could never conclusively reach an agreement. However, as of January 2021 – four and a half years after the Brexit referendum – Britain is finally no longer a part of the European Union. This has many implications, but most broadly – and perhaps most importantly – it means that they are no longer bound by the European rules. They can now impose laws that the European Union would not necessarily agree with, as exemplified by one of their first moves: the removal of the controversial ‘tampon tax’.

To the disbelief of many, sanitary pads and tampons are not considered ‘essential goods’ in the eyes of the European Union. Many activists have fought this, citing that women cannot possibly control their periods and should not be taxed for a natural phenomenon. The tampon tax would increase inequality between men and women. Others claim that if taxes have to be paid on things like toilet paper, bread, bottled water, medication and diapers, they can also get behind a tax on menstrual products. Either way, because menstrual products are not considered essential, member states of the European Union are required to tax these products at a minimum rate of 5%. For example, in the Netherlands menstrual pads and tampons are considered ‘bandages with a medical purpose’ and are taxed at 9%. This is the same rate and reason that is used for band-aids, cotton pads, first aid kits, splints, etcetera. The 9% is considered a lowered tariff for certain essential products and is also the percentage used for most foods. The tariff for all other products – which are considered luxury items – is 21%. Most European countries use a similar system of both a low and a high percentage. However, in many countries, menstrual items are taxed as if they are luxury goods: Hungary taxes menstrual products at a whopping 27%, Denmark and Croatia both tax 25%.

In 2013, British activists began campaigning for the removal of the ‘tampon tax’. Britain responded by saying that it was unable to lift the tax, because of the European regulations. When Brexit-mediations began, the tampon tax became a topic of discussion. Amid the negotiations, the European Commission decided in 2016 that as of 2022, member states would be allowed to decide whether or not they wanted to tax menstrual products. This revived the discussion and resulted in many countries lowering their tax tariffs on menstrual products. In 2005, a Belgian women of parliament calculated that her government gained 20 million euros in luxury tariff tax revenue on menstrual products a year. It still took Belgium until 2018 to finally lower the tariff. In 2015 a law to lower the tariff on sanitary pads and tampons was unable to pass through the French parliamentary for the single reason that lowering the tax would result in a 55 million euro decline in tax revenue. Germany followed suit in 2019 after activists published a tampon book filled with 15 tampons, as books were considered an essential item and were taxed at a lower tariff than menstrual products.

Now, here’s the thing: I don’t necessarily mean to advocate a zero-sum tax on menstrual products. Frankly, if toilet paper and foods are taxed, why would menstrual products not be? I do not choose to bleed, but neither do I actively decide to be hungry or to have to use the restroom. Nevertheless, I do advocate a low-tariff tax on menstrual products, as it should be clear to everyone that menstrual products are definitely an essential good and not a luxury item. If books and goldfish are listed as essential items and are taxed at a low rate, why would menstrual products be considered non-essential? From a government’s point of view, I get it. Women need menstrual products regardless of their price, so it’s an easy product to get a large tax revenue from. One way or another, taxes are an essential part of a social welfare state. Tax revenue is needed to pay for many things. However, the fact that the government tries to make money off products that every women needs regardless of the price – and even admits to it, as in the case of France – really rubs me the wrong way.

In 2019 Scotland made a bold move by making all menstrual products freely available in an attempt to reduce period poverty. Research has shown that a lack of access to menstrual products is a large reason for young girls to miss school or work. In a Dutch research from 2019 it was revealed that one in nine women (ages fifteen through twenty-five) sometimes do not have enough money to pay for period products. Similar to the taxing problem, I do not actively advocate free menstrual products. Making it completely free is hard, as making the items costs money. Also, there is a market for these types of products: some women prefer pads with wings, others prefer longer pads, black pads, undyed cotton pads, thinner panty liners, or pads shaped specifically to fit a thong. Others prefer tampons, which come in many different shapes and sizes. There are so many options available that making them free would very likely limit the possibility of using an item of preference. However, I am a strong advocate of including menstrual products in the food bank system. Women in need sometimes miss school or work because of a lack of access to female hygiene products and I think making these items available to them through food banks would help solve this issue.

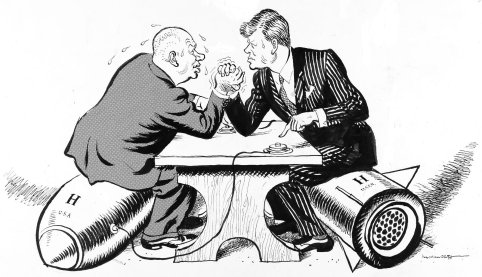

However, what I do mind is the usage of this tax for political reasons. As might have become obvious from above, many countries lowered their tariffs in response to the Brexit-negotiations. It is very likely that these countries will rid themselves of the tax altogether as soon as they are allowed to do so in 2022. However, they will be doing so solely for political reasons. Suddenly, Britain is praised for its equality policies and Brexit is seen as this great thing to happen to Britain. Britain used the female reproduction organ as a way to show the rest of the world how amazing they are when in reality there are so many more things they could have done to deal with the problems of equality and poverty. The removal of the tax is a relatively cheap, and most of all completely symbolic policy that will have no real effect. Research indicated that the removal of the tax would result in a six to eight cent price difference on menstrual products. Many stores might not even change the prices and simply pocket these few extra cents themselves, as women are already used to paying a certain price for their products and a few cents is not going to result in any real differences. If more countries get rid of the tax in 2022, Britain will get to say ‘look at what we did, look at all these countries following us’. They will undoubtedly paint it as a fuck you to the European Union. This policy had nothing to do with equality or poverty. It had everything to do with Britain’s attempt to show they are more powerful than the European Union.

Why Britain getting rid of the tampon tax has nothing to do with women